While preparing this piece, I came across a page of notes on Saga, Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ long-running space fantasy comic, for a Space Opera Week that for some reason I was convinced never came to fruition. Imagine my surprise when I realized that not only did Tor.com definitely explore the corners of space opera back in 2017… but I wrote about chasing hope across the universe in none other than Saga.

Blame it on baby brain. But here’s the thing: It’s been almost six years since then, with three more Saga trade paperbacks published in the interim (around a hiatus from 2018-2022), and I might as well be reading this series for the first time as a longtime BKV fan and newish parent—through a route much more convoluted than Marko and Alana’s, yet with a surprising number of parallels. That’s what makes Saga endure so well: Like Hazel, it grows into something new with every break and return, and its place within our comics universe—and its readers’ own personal universes—shifts. Having celebrated its ten-year anniversary a year ago, it hasn’t abandoned its opening line (This is how an idea becomes real), but rather has embraced how it’s not as simple as releasing an idea into the ether; you have to nurture it, even when you feel that you can’t possibly do so, to ensure its survival. And, most crucially, you have to let go of your expectations for what ideas your idea wants to create.

Spoilers through Saga Volume Ten. Content warning: (in)fertility, pregnancy loss, abortion.

Saga is space fantasy at its most unabashedly imaginative: Its characters have horns and wings, or they’re anthropomorphic seals and royal robots and ghost babysitters and feline lie detectors. They live in organic tree spaceships, or on comets racing across the galaxy to planet-sized eggs that hatch into babies that suck everything away. They use secrets to power spells, and shoot guns that break your heart. They communicate through rings imbued with translation magic, or through subversive texts masquerading as romance novels.

Yet despite all of this unique worldbuilding, Saga hinges on the kind of convenient plot twist utilized in soap operas but really across all genres: the accidental pregnancy that changes everything. When these soldiers and nobles and civilians are caught in The Narrative of war, it takes a universal trope to shake them out of their complacency or their blind hatred: An accident that becomes an act of subversion that becomes an idea that becomes a baby that becomes a hybrid that becomes Hazel.

But just because Hazel is so wholly herself, doesn’t mean that she’s a singular impossibility or a quirk of genetics. In fact, Marko and Alana’s union is literally fertile ground, in that every time they come together (heyo) they manage to conceive a new life. Despite the series’ penchant for attention-grabbing splash pages full of sexy times, there’s something very wholesome about this, in watching their meeting of minds (and, er, other key parts) consistently spark a new and dynamic idea.

I know plenty of couples who have experienced this variation on a good problem to have, who have gotten pregnant on a faster timeline than anticipated and have had to pivot their entire lives around something that is rushing at them before they actually think they’re ready. Their lives transform in the blink of an eye, their responsibilities shift and their identities morph. And they’re maybe still processing this mere notion when it’s suddenly a defenseless person squalling in their arms, and they haven’t slept in days and/or might be leaking all sorts of fluids and emotions. Life happens to them, and they have to react to this new normal.

By contrast, my husband and I knew about our child when he was nothing but an idea, insubstantial and uncertain and in no way guaranteed: Fertility clinic schedules and monitoring ultrasounds and injections (so many injections, over sushi takeout with friends and in airport family bathrooms), all during the height of covid. A surgery (egg retrieval) the likes of which I’d only ever seen in sci-fi series like Battlestar Galactica, depicted as a nightmarish scenario in fiction, but in real life a much-needed scientific intervention. Daily phone calls detailing the “hunger games” of twenty-two eggs whittling down to just two embryos in petri dishes. A transfer in which I literally watched the air bubble that contained our embryo, our little wish, float into my uterus like a ship tracing its way across the blackness of space. Our doctors sent me home with a photo of our embryo just beginning to hatch and the instruction to laugh as much as possible because the contractions would help with implantation.

Buy the Book

Some Desperate Glory

With all that, it’s wild to imagine two people conceiving simply after a meeting of D. Oswald Heist Book Club, or after running down a lead in finding their kidnapped daughter. Making an idea is the easy part for these warriors-turned-parents; keeping that initial spark from getting snuffed out—by people who have political motivations to hide its impact, or who simply have been carrying a personal grudge since Hazel was conceived—becomes their life’s work. Even, and especially, when the thrill is replaced by the tedium.

Some of the most imaginative parts of Saga are also the most quotidian: You have to clothe a baby (and do nigh-infinite loads of laundry during the early months of constantly spewing bodily fluids), so Vaughan and Staples came up with a tree spaceship that generates the fibers for Marko’s father Barr to weave into clothing for his surprise new family members. There’s a period of a couple years where they hide out on another planet, Alana playacting on the local soap opera and Marko playing house husband, taking Hazel to playdates and dance class, anonymous beneath bandages. Isn’t that how it goes—you could be a war hero/criminal wanted on every planet, but parenthood flattens you into just another dad at the playground.

I remember reading a post on a subreddit or elsewhere that sneered at new parents’ tendencies to post monthly growth photos on an Instagrammable mat, or to detail the little one’s latest preferences—something along the lines of, of course baby likes to roll at x months, ALL babies do that! But that impression remains, that your baby is doing something absolutely unique at a time in your life that affects you, no matter if millions of other babies are doing the same thing elsewhere in the world (or universe). And Vaughan smartly lines up Hazel’s otherwise ordinary milestones (first words, first buddy, first favorite book) with key events in the series, cementing the ordinary moments among the extraordinary backdrop.

Even though I’ve reread this series multiple times, I still have to jog my memory as to what comes when in the narrative. But I’ll never forget the visual of Hazel, squished between her parents in a moment of tension, gleefully exclaiming her delight in one word: skish. It’s what we call our son, and how we check in during the most stressful moments. We skish.

This is how an idea becomes real is how Hazel introduces herself in voiceover, in retrospect, as Alana bears down on another contraction and delivers her in an abandoned auto shop on a planet swarming, with both sides trigger-happy and out for blood. But I would respectfully disagree that Hazel was already real the first time that Marko and Alana met, the first time she passed him her copy of A Night Time Smoke. She just wasn’t alive yet.

This distinction becomes more real when her parents conceive a baby brother, and then lose him in utero during an awful battle with one of the many interlopers who would threaten their family. But Alana is far enough along that her body can’t pass the tissue, so they land at one of the series’ most surreal and most memorable settings: Abortion Town, where a mother wolf out of a dark fairy tale grimly performs the late-term abortion of a very much-wanted child.

But before that, the magic that Alana and Marko’s son Kurti might have possessed manifests itself as a Forecasting spell, projecting a little boy for Hazel to play with on their journey to Abortion Town. She gets to experience a potential future with a sibling—to witness her parents’ ideas at work—even knowing that her brother will never be born. Even from a young age, Hazel has always understood how fragile the future is.

Hazel narrates from adulthood; from the first pages, we know that she gets the ultimate gift of growing old. Not everybody does is how she ominously ends the very first chapter, on a family portrait of Marko and Alana embracing with their daughter between them. Since 2012, we’ve known that at least one of her parents would die young. Or perhaps she’s talking about her baby brother, who was years away from being conceived in that moment, but was an idea the way the egg that became my son was once just a possibility.

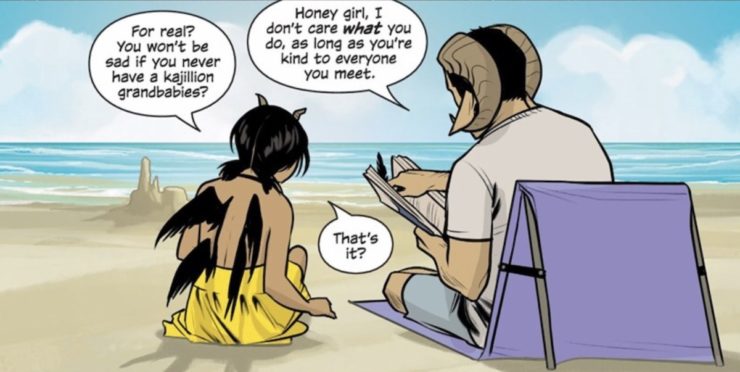

But in Volume Nine, Hazel closes that narrative loop, as The Will murders Marko in a showdown years in the making, in a spaceship that looks like a diamond mated with a jellyfish. Looking down on the family he’s created, that he has to leave behind long before he’s ready, Marko’s final moments are recalling perhaps his most important conversation with Hazel: She knows, from this precocious age, that she doesn’t want children. They’re playing on the beach in a rare moment of peaceful stillness, and she’s scared to confess that she doesn’t want to give him grandchildren someday. Hazel can be aware that she represents an end to the war by showing what these opposing sides can make by working together, yet that does not automatically make her some sort of space-Eve, some obligatory progenitor of a new hybrid race. “I’m so, so glad you guys made me,” she says. “But I maybe want to make other stuff.”

And he says all he has to, with one word: “Awesome.”

And Hazel brings things full circle by repeating her opening monologue: My name is Hazel. I started out as an idea, but I ended up something more. Not much more, to be honest. It’s not like I grow up to be some great war hero or any sort of all-important savior… but thanks to my parents, at least I get to grow old. Not everybody does.

That was in 2018, a year before my husband and I started trying, before we realized with mounting dread that this idea we could see so clearly in our minds might never become real the way Hazel means it. Saga sat untouched on our bookshelf.

Finally, in 2022, Saga returned with Volume Ten. For us it had been four years since Marko died, three for Hazel and Alana.

This is how an idea survives, Hazel reintroduces herself in the opening, as a ten-year-old aspiring magician running from people who would kill her for her horns without even knowing about her wings. Her mother has had to return to the wolf abortion doctor, who permanently removes her wings—the beautiful wings that she passed down to her daughter—so that she can move through the universe without people suspecting who she really is.

And life goes on. And parts of it are still dull and humdrum. Alana and Hazel are smugglers (or, as she learns later, drug dealers) scraping by. Alana fucks a dog-person because he’s a fellow widower, and gets fleas. Hazel experiences new milestones, like navigating a weird crush from her adoptive brother Squire, like her own first love: guitar.

Hazel watches their home, their tree spaceship, go up in flames, finally losing her last tie to her father, and finally grieves outliving one of her creators. And life goes on.

A space opera can feel mundane as shit. The everyday can feel like science fiction. This is the magic of Saga.

No, Natalie Zutter did not name her son after The Will. Share the most wonderfully mundane bits of SFF with her on Twitter!

Wow. Thank you for bringing another layer of insight to a book I already love.

Also: utmost appreciation & respect at baring some deeply personal life experiences; thank you for sharing.

Additional also: The Will is quite the geebag alright.

Totally not tearing up at work. Thank you.